If my school experience was to be believed, I simply had to know and pursue the career path I picked as soon as humanly possible. I took aptitude tests, I read about various jobs and potential salary brackets, and I boldly stated in around eighth grade what I planned to be when I grew up.

I loved writing, reading, research, and learning. I also loved anything involving creativity, including writing and art, but, “Those couldn’t possibly be ‘real’ jobs,” the adults said. So I found something practical. After all, financial security and stability are paramount.

So, I wrote a story. I was smart and capable, but I didn’t like blood or the potential risks of seeing or potentially causing death. Medicine and veterinary science were out.

But I was good with words, such a quick study, thought on my feet well, and loved the one mock trial elective I took at the school I got shipped off to once a week to get additional learning enrichment (and perhaps to avoid distracting other classmates because of boredom). More school didn’t bother me, but I didn’t want to teach students, because it seemed like I would be in a perpetual Groundhog Day scenario each year.

Thus, I mentally invested in persuading myself that I wanted to become an attorney. “What, like it’s hard?” as Legally Blonde’s Elle Woods so eloquently (and naively) stated a few years down the line.

The plotting of my story started with telling myself various inciting incidents made becoming an attorney a foregone conclusion. I did that from the initial choice and then every time I doubled down on it, including when I applied to law school and interviewed for jobs. These went something like:

- My family had experienced a medical malpractice scenario during my sister’s birth and while nothing could reverse course, the legal system could help prevent others from experiencing the same;

- I have a deep respect for rules and social contracts, and laws are the basis on which all of that depends;

- I grew up in a family business, making me very aware of all the legal needs businesses have to operate;

- I want to help people navigate difficult scenarios and get to the best feasible outcomes;

- I love problem-solving and finding the answer to hard questions through research and analysis; and

- Our country is the great democratic experiment and laws and rights are the foundations on which it is built and endures.

Note, none of those lofty ideals said, “I understand the role of an attorney and am deeply interested in stepping into that role to represent clients in and out of court, including filings, hearings, oral arguments, and more.”

The simple truth is that I did not know what to expect from the law. I had not shadowed anyone. I never worked at a firm before my first attorney job. I loved how it developed and the stories it told, but as a graduate assistant and legal intern, I gravitated toward soft skills and presentations that did help (and in fact were teaching) people, but I feared the inevitable court part of it all. I never took trial advocacy because over 90 percent of cases settle, right? Court is a rarity. Right?!

But let me back up a bit. I went through college majoring in political science, because it seemed like the “right” preparation. But then I also couldn’t stop adding English and French courses, among other electives. I found creative outlets, so I endured. I took logic classes and philosophy, doing all the preparatory groundwork to show I had the ability to think like a lawyer and ace the LSAT.

I got in and continued with law school, not necessarily enjoying myself, but I continued because it was what I had chosen and I wanted to show I could do well. I added electives that spoke to me (art law, photography, lawyers and literature, animal law). I found ways to endure and achieve good results yet again.

It was always the plan above all else. I had been taught once you make a commitment, you don’t quit. You see it through. So, I did.

I signed up for the bar two days before the late filing deadline. I didn’t want to be an attorney but a “scared straight” job interview moment made me realize I had prepared for no alternative. So, I got back in line with the plan.

I wanted a job with my graduate assistantship’s office, or, if not that, in property, contracts, or business. I wanted as far away from litigation as possible. But, the job market was a mess when I was in school and as I was graduating, so eventually I let my resume and chips fall where they may. I told the stories I needed to tell for the audiences I was in front of. I ended up in administrative law and litigation. I wasn’t supposed to be in court for at least a year. I ended up in court and hearings in less than six months.

I could write a story. I could become who I needed to be to get the job, or the assignment, or the good review, or the best possible outcome for the case. I could shove down the imposter syndrome and do what was asked of me. I could struggle with finding my place internally, but externally, I had myself covered. I molded myself into the character I created.

The story held, until it couldn’t. The plot holes formed at first when my first child was born. I tried soothing the creative itch and the unease with photography and creating on the side, and it helped. But it couldn’t solve the travel, the schedules, the stress, the disconnect between being a mom and being who I plotted myself to be.

So, I found a different role and pivoted to a schedule less likely to lead to court. I stepped into a writing-heavy role that kept me an attorney in name. But when I found myself writing the same stories over and over, I found ways to branch out by teaching others how to write and analyze cases (which I truly enjoyed). I supervised for a bit, still teaching, training planning, and mentoring with the added bonus of having some dominion over how I did those tasks. I also got to plan events, work in hiring, analyze office feedback, market our services, create presentations, and make at least some creative writing and design projects a part of my everyday life.

But I loved being challenged intellectually and figuring out how to solve big problems. So I wrote another role in my head—the one where I pivoted more directly back into law. Where the status of the role communicated how much I could do, could be. This was success, was it not? To be in a role that so many wanted to chase?

I applied and interviewed. And I told more stories—my whys, my hows, my wants. I sold myself as the person they wanted to see (both to them and to me). I was the solution. I was capable. I was an asset. And then, I accomplished the dream.

Except, after the initial allure of learning so many new things, figuring out the office and client needs, mentally filing away the pieces that would make me a success, that gilded role of attorney I had written, admired, and forced myself to chase wasn’t all that beautiful up close. I continued to enjoy being the kind face of the office, teaching, connecting with colleagues and clients, and selling its stories. Yet, with the legal work, the stress and the pressure to constantly fit within the mold and sell myself in a role that I never felt was me kept cracking away.

The gilding wasn’t gold. It was fiction. Fiction wrapped around the picture of an attorney, framed and collaged together over years of persuading myself that I could do this, I could be this person, what people wanted and needed because that was the plan. Maybe I was pretty great at persuading after all—look how well I convinced myself for so long to be all these things over and over again.

And when things felt hard, I still didn’t wake up. I turned on myself, not the role, not the offices, not the ever-increasing expectations as colleagues left and workloads were absorbed. It must be a character flaw, my self-assessed failings. It couldn’t be the workload or something or someone else. I felt I was failing and I just couldn’t let myself fail (though the reviews never reflected that story at all). I had to make myself fit the character I’d artfully written and committed to. What other choice did I have?

This is the part of the book where the screaming at the narrator or main character starts—quit telling yourself the misbeliefs! Change something! Take a risk! Ditch the plan! Why isn’t she seeing it? Damn it, wake up!

And yet the main character’s inner turmoil and conflicts pop up—can I change? Can I do anything? Is it too late? Is there anything else? Maybe there’s nothing else? There’s nothing else! No amount of side quests or creative outlets could out-shadow the problems. The main character sinks into her dark night of the soul.

And then I realized nothing changes if nothing changes. I sought and got help. I found wise teachers (read: mental health professionals and loved ones) that helped me really see the narrative I had been telling myself for what it really was. I learned. Facing all those stories I told myself was really hard, but it became incredibly clear that it was necessary.

It is gut-wrenching to look at the structure in a manuscript and realize one or more fundamental building blocks aren’t working. To acknowledge that if this would-be book is ever going to work, the parts must be ripped from the whole, if there’s anything to be salvaged. To see beyond the initial character sketch, goals, conflicts, and stakes and see what works and what doesn’t, and what it could come to be, if it could just be edited and refined, especially as we learn and grow.

It’s so tempting to doggedly continue, hoping something eventually clicks in the end. Self-editing is hard. Seeing work, life, from a different perspective takes a self-awareness and a willingness to ditch the plan and revise what isn’t working. It takes a level of honesty that burns and chafes. It tests stubbornness and what pieces are worth fighting for or what can be sacrificed if only there’s bravery enough to take a risk and see what could be instead of what currently exists.

But there might be beauty and brilliance within the pages if they can finally shine through when not obscured by the pieces that need cut away, rewritten, or relocated. If perhaps, they could reflect a more authentic me.

Sometimes my story feels Elle’s in reverse from law to something more creative (whatever may come to be). I can’t help but feel, though, the underlying message of her character arc stated so succinctly in her graduation speech is consistent with what I hope to do:

It is with passion, courage of conviction, and strong sense of self that we take our next steps into the world, remembering that first impressions are not always correct. You must always have faith in people. And most importantly, you must always have faith in yourself.

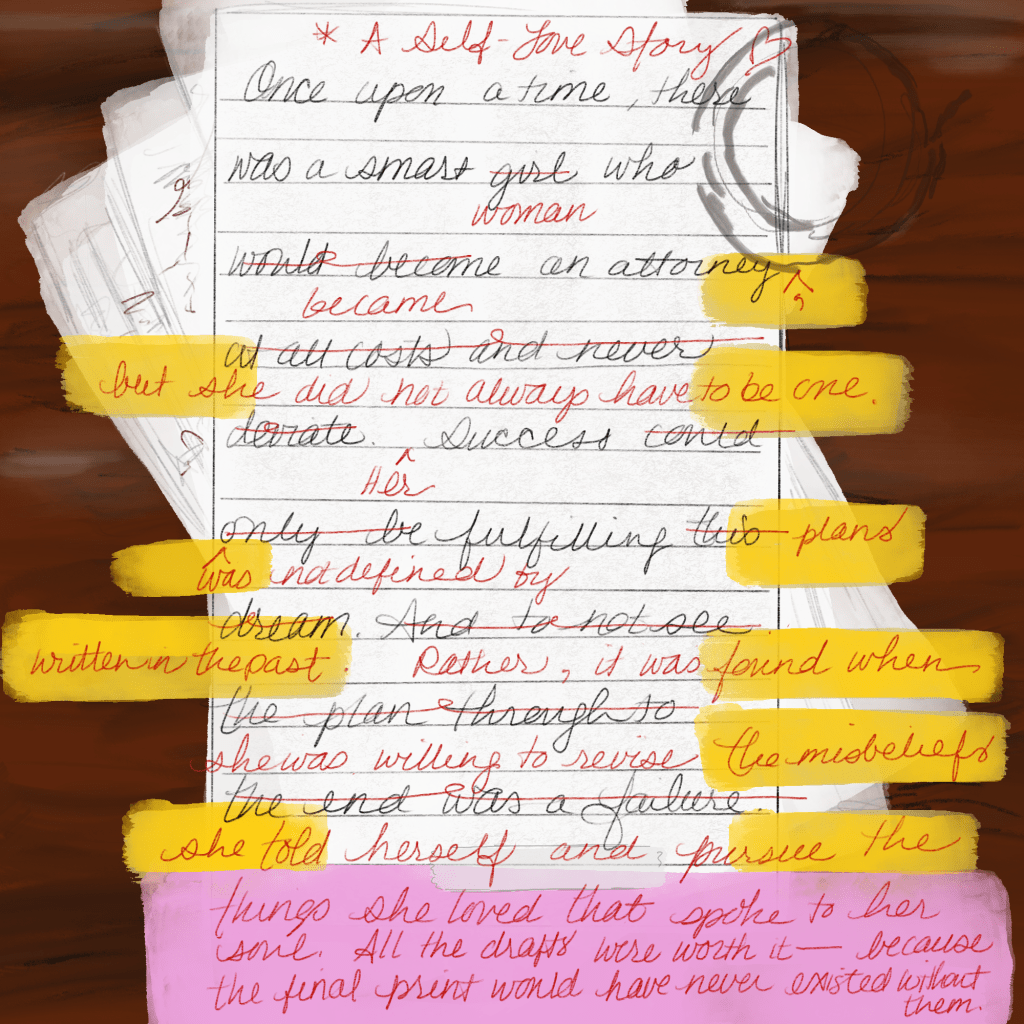

I’m finally drafting and creating a different story—one that started with going to law school and being an attorney, but it doesn’t end there. Instead, I’m looking for what could be instead of what I once believed I “should be” as authored by a past me who didn’t have the life experience or world view to realize how much deeper or varied the options could be. This need for revision isn’t a failing, but a rebirth and endless potential of what could be and is to come.

It’s not a total loss, it never is. The parts that work will remain. The life experience and skills always endure and will continue to grow and transfer. But now, with those edits, with the willingness to change the plot, there’s room for my story to become hopefully what it’s meant to be. Even though more edits are inevitable and needed to let my story develop, this is the arc I want to keep drafting and creating, plot twists, character growth, and all.

Leave a comment